Offensive BPF! Getting started.

Over the last few years eBPF has gained a lot of traction in the Linux community and beyond.

eBPF’s offensive usage is also slowly getting more attention. So, I decided to dive into the topic from a red teaming point of view to learn about it to raise awareness and share the journey.

Similar to the format of my Machine Learning Attack Series, there will be a serious of posts around BPF usage in offensive settings, and also how its misuse can be detected.

Click the “ebpf” tag to see all relevant posts.

So, let’s get started.

What is Berkeley Packet Filtering?

Classic BPF allows a user space program (e.g., tcpdump) to receive certain network packets based on a provided filter. The actual filtering is run inside the kernel. This greatly improves performance because only packets that pass the filter need to be copied to user space.

What makes eBPF extended is that it is a general purpose technology for tracing and hooking.

It is used to safely and efficiently extend the capabilities of the kernel without requiring changing kernel source code or load kernel modules. (ebpf.io)

Nowadays, when people talk about BPF, they typically refer to the newer, extended version (rather the classic BPF), so I will just use the term BPF going forward.

BPF allows users to write small, sandboxed programs that run inside the kernel.

BPF Use Cases

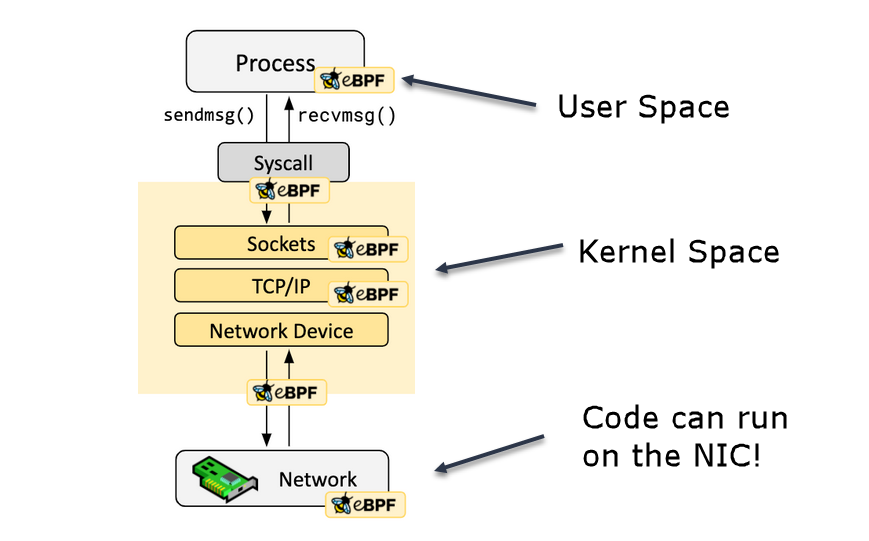

It is possible to run BPF programs basically anywhere in the kernel or user space, and even directly on network cards that support it.

Note: Modified image (original image from https://ebpf.io)

Being able to offload BPF programs to a NIC is interesting for offensive security reasons. This means that the program runs on the NIC, and the kernel can only process packets after the BPF program ran.

The core use-cases are tracing, observability, perfomance measuring and security tooling.

A lot of the latest detection, monitoring software and performance tracing tools are written in BPF and in the cloud native space BPF is seeing a lot of adoption (e.g. Cilium).

BPF programs, Maps and Events

The BPF infrastructure is made up of a set of core paradigms.

The foundational pieces are:

- BPF Programs: Typically written in a C-like language and compiled (JIT) to BPF byte code.

- Maps: Communication between kernel and user space happens via these data structures.

- Events: The programs are run upon events (e.g., entry/exit of kernel functions).

BPF programs allow us to run user programs in kernel space. They are like flexible light-weight kernel modules. But compared to kernel modules, they have much higher reliability guarantees.

A dedicated Verifier makes sure that they are stable and will not crash the operating system.

Loading BPF programs

A BPF program is loaded into the kernel by a privileged user using the bpf() syscall.

The call requires root or the CAP_BPF capability for most BPF program types (see Appendix).

The loading of a program goes approximately like this:

- Load: A user space program calls

bpf()using theBPF_PROG_LOADparameter to load the program (it might also create maps, if needed). - Configure: The user space program associates the BPF program with events/probes. For instance via

ioctl()calls (e.g.PERF_EVENT_IOC_SET_BPF). - Execute: Now, whenever a trigger event occurs, the BPF program will run in the given context!

All this gives developers (and attackers) great flexibility and power.

Non-persistent: BPF programs are not persistent across reboots (so they have to be started again).

Offensive BPF - The alternate use case!

BPF is interesting from an offsec perspective, because BPF programs have superpowers and from what I know so far they can:

- Hook into syscalls and user space function calls a like

- Manipulate user space data structures

- Overwrite syscall return values

- Call system() to spawn a new process (built-in

bpftracefeature) - Some BPF programs can be off-loaded to hardware devices (like network cards)

- New opportunities for supply chain attacks by targeting BPF code

- Mingle with security and detection tooling (e.g., by hooking the

bpfcall itself)

An Offensive BPF program is one that might install itself as a rootkit on the machine, and BPF has also been used to succesfully break out of containers.

Quite exciting, and some great opportunities to perform red teaming ops to help raise awareness and detection capabilities.

Getting Started

There are three levels of sophistication for using/building BPF programs:

- Level 1: Live off the land and use existing BPF programs, e.g. there is

sslsniff-bpcc. - Level 2: Write you own little malicious programs and run them with

bpftrace - Level 3: Write more complex programs using libbpf and other lower level frameworks. Compile to BPF bytecode via tools like

clang.

One could also write BPF bytecode directly, which might be Level 4. :)

My goal is to explore each of these in more detail (some of them I have already) and post about outcomes and learnings.

Learning Resources

To conclude this initial post, I wanted to shrae the most useful resources I used to get started.

For general BPF information, sample code and code snippets I find the talks from Liz Rice and Brendan Gregg extremely useful - their talks help you understand what BPF can do and how it is used for good:

- A beginners guide to eBPF programming, Liz Rice GOTO 2021

- BPF performance analysis at Netflix, Bredan Gregg, 2019

On the offensive side there is not yet a lot of content, but these three talks are high quality:

- DEFCON 29 - eBPF, I thought we were friends, Guillaume Fourndier, et al.

- DEFCON 29 - Warping Reality, @pathtofile

- DEFCON 27 - Evil eBPF Jeff Dileo, NCC Group 2019

All these talks provide great insights and are very informative.

Cheers.

PS.: Any feedback or ideas, feel free send me a message

Resources

Appendix

There are different types of BPF programs, like TRACEPOINT, KPROBE, XDP, PERF_EVENT.

Some programs can be created by a low privileged user:

BPF_PROG_TYPE_SOCKET_FILTERBPF_PROG_TYPE_CGROUP_SKB

To see if unprivileged BPF is enabled/disabled is:

cat /proc/sys/kernel/unprivileged_bpf_disabled

Change via:

sudo sysctl kernel.unprivileged_bpf_disabled=1